[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Neotropical Whipsnake (Masticophis mentovarius)

[/vc_column_text][gap size=”12px” id=”” class=”” style=””][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”2110″ img_size=”large” alignment=”center” style=”vc_box_rounded”][vc_column_text]Neotropical Whipsnake, Sierra de la Madera, northern Sonora. Photo by Jim Rorabaugh[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”2420″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”img_link_large”][vc_column_text]Neotropical Whipsnake, Rancho El Aribabi, Sierra Azul, Sonora. Photo by Sergio Avila[/vc_column_text][gap size=”12px” id=”” class=”” style=””][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”2417″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” style=”vc_box_rounded” onclick=”img_link_large”][vc_column_text]Neotropical Whipsnake, Sierra de la Madera, Sonora. Photo by Jim Rorabaugh.[/vc_column_text][gap size=”12px” id=”” class=”” style=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_column_text]

Description

Editor’s Note: In a genetics study, Myers et al. 2017 (Copeia 105(4):642-650) concluded that all

New World racers and whipsnakes should be in the genus Masticophis except for Coluber

constrictor.

The Neotropical whipsnake (Coluber mentovarius, C. Dumeríl, Bibron, and A. Dumeríl, 1854) is a relatively robust racer or whipsnake well-known in Latin America from Sonora and western Chihuahua, Mexico south to Venezuela and Colombia. The species has often been referred to as “Masticophis mentovarius”, and in older literature as “M. striolatus”, “M. lineatus”, or “M. flagellum striolatus” in regard to specimens from Mexico. This account follows the nomenclature recommended by Utiger et al. (2005) and accepted by Liner and Casas-Andreu (2008).

Figure 1: Adult Coluber mentovarius from 11.7 km E of Yécora. Note the 8 supralabials and presence of a loreal scale. This individual also possesses traces of several light crossbands on the side of the neck. Photo by G. Ferguson.

Description: Throughout its range, this species is large (to 2527 mm total length) with a long tail (23-36% of the total length). The dorsum in adults is brown, tan, gray, or bluish-gray with no prominent striping. Individual dorsal scales often have dark spots that can suggest narrow linear stripes. The top of the head may be tan or brown, and the underside of the head and chin ranges from being devoid of markings to heavily mottled, depending on the subspecies. Juvenile snakes may possess anterior crossbands or longitudinal stripes. Scutellation is as follows: 6-8 supralabials on each side of the head, smooth dorsal scales in 16 or 17 rows at mid-body; 166-205 ventrals; and 95-123 divided subcaudals. The loreal is present (Johnson 1977, Savage 2002).

Subspecies: Johnson (1977) recognized 5 subspecies. Coluber mentovarius striolatus is found from Sonora and western Chihuahua south to Jalisco and Michoacán, Mexico. C. m. striolatus typically has 8 supralabials on each side of the head (8+8), the fourth and fifth of which border the eye; 17 scale rows at mid body; and usually less than 190 ventral scales. Dorsal color is tan to gray or blue-gray; individual dorsal scales of which may or may not have a dark spot or stripe. Ventrally this subspecies is cream-colored with varying degrees of pink or salmon on the posterior portion of the body and tail. Mottling on the chin and sides of the head is lacking, and the top of the head is tan or brown. Johnson (1977) reported that the dorsal pattern of juveniles is reddish-brown anteriorly, which grades to light brown posteriorly; however, based on limited material (2 live juveniles), we have not seen this pattern in Sonora (see below). Anteriorly, the dorsum in juveniles is characterized by 15-18 light crossbands that may be outlined in black. The dark spot or stripe on each dorsal scale may be absent in juveniles (Bogert and Oliver 1945, Hardy and McDiarmid 1969, Johnson 1977).

Figure 2: Adult Coluber mentovarius (same individual as in Figure 1). Note the faint stripes on the dorsum. Photo by G. Ferguson.

One of us (JR) examined 15 Coluber mentovarius striolatus specimens from Sonora in the University of Arizona herpetological collection. Total length of complete specimens (n=13) ranged from 1156-1783 mm (mean = 1471 mm). Tail length was 23-29% of total length (mean = 27%), which is less than Savage (2002) indicated for the species (32-36%). All specimens (n=15) possessed 8+8 supralabials, except UAZ 25710, which had 8 supralabials on the left side and 9 on the right. The fourth and fifth supralabials contacted the eye on all specimens. All had 1+1 loreal scales. The top of the head of each specimen was colored tan or brown, some which were infused with dark mottling. Each specimen had a dark spot on the posterior of most of the dorsal scales, or a dark stripe through those scales. Dorsal spots typically began 10-20% of total length behind the snout and became more pronounced posteriorly, often taking the form of dark stripes through the dorsal scales at mid-body and anterior to the tail. These dark spots or stripes faded on the tail and were absent at and near the tail tip. The underside of the head and chin was cream-colored and immaculate or nearly so in all specimens, as was the ventral side of the snakes. Any ventral pink or salmon color that had been present in life was absent in the preserved specimens. Only one specimen was a juvenile (UAZ 46782), and only the head and neck were collected. The neck had several light crossbands, which faded or disappeared towards the middle of the dorsum. Several of the adult snakes possessed traces of this juvenile pattern, including light bands that extended upward from the ventral scales 1-5 scale rows (also see Figure 1). These bands typically began immediately posterior to the supralabials and numbered up to 17.

GF examined a live specimen (Figures 1 and 2) from near El Trigo, 11.7 km E of Yécora, that measured 1160 mm total length, of which the tail was 28% (320 mm). It had mostly 17 (18 at one point) scale rows at mid-body, 8+8 supralabials, of which the fourth and fifth contacted the eye (Figure 1). The dorsum was blue-gray with a dark spot on individual scales, and faint light and dark stripes were present (Figure 2). The venter was cream-colored anteriorly, grading into a bright salmon color on the posterior of the body and the tail. Two live juveniles, one from Rancho El Aribabi, ENE of Imuris (photographed by C. Robles Elías) and one from near Yécora (photographed by T. Van Devender and A. Reina G.) resembled adults, except that the anterior light crossbands were somewhat bolder and some were complete across the dorsum, dark spots and stripes on the dorsal scales, as well as the contrasting brownish color atop the head, were reduced, and the light and dark patterns on the supralabials and preocular and postocular scales, were quite bold (see Figure 1 for the expression of this character in an adult).

Similar Species: Two other species of Coluber (C. bilineatus and C. flagellum) occur sympatrically with C. mentovarius in Sonora (Rorabaugh 2008) and western Chihuahua (Lemos Espinal and Smith 2007). Coluber bilineatus is conspicuously striped and has 15 scale rows at mid-body. Coluber flagellum has mottling on the chin and throat (absent in C. mentovarius striolatus from our area), and lacks the distinctive and contrasting brown or tan coloration atop the head characteristic of C. mentovarius. Juvenile C. mentovarius and C. flagellum both have crossbands anteriorly, but juvenile C. flagellum have a light crossbar on the nape of the neck and brown-centered labials (not so in juvenile C. mentovarius, Lemos Espinal and Smith 2007). Ventral scales usually number <190 in C. mentovarius and >190 in C. flagellum. Coluber mentovarius is a more robust snake with a broader head than either C. bilineatus or C. flagellum.

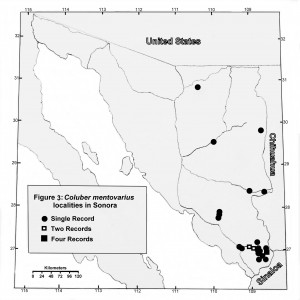

Distribution in Our Area: Twenty-four museums were queried for specimens of Coluber mentovarius from Sonora. We also interviewed others working in Sonora and reviewed distributional literature for this species. Figure 3 displays the distribution of C. mentovarius in Sonora based on 23 preserved specimens, one from field notes of C.H. Lowe on deposit at the UAZ, four photo vouchers at the UAZ, and two reliable sight records that help define the species’ distribution in Sonora (Highway 14, 21 km NE of Mazocahui, Stephen Hale, pers. comm. 2008; and 11.7 km E of Yécora, George Ferguson – see Figures 1 and 2). Twenty-seven of these 30 records are from Highway 16 south through southeastern Sonora. All but seven of those are at or in the vicinity of Navojoa, Álamos, Río Cuchajaqui, Choquincahui, and Güirocoba; we are aware of additional sight records for these areas. Three records exist for northeastern Sonora, including “Cueva Creek near Tres Rios” (Tanner 1985, Lemos Espinal and Smith 2007); Highway 14, 21 km NE of Mazocahui; and Las Palomas, NW slope of the Sierra Azul, Rancho El Aribabi, ca. 27 km ENE Imuris (UAZ 56736-PSV [Figure 4], Avila et al. 2008). The latter locality is about 159 km (99 miles) from downtown Tucson, which places it within the Tucson Herpetological Society’s “100 mile circle”. Two or three additional specimens of C. mentovarius were observed at Las Palomas by S. Avila on 24 May 2008, and a juvenile was observed by C. Robles Elías on 4 November 2008. The species was first collected in Sonora in 1941 (at Güirocoba, AMNH R63721). Lemos Espinal and Smith (2007) list three localities for C. mentovarius in Chihuahua, including Chínipas, La Mora, and Moris, all of which are in the southwestern portion of the state near the Sonoran border. A specimen from extreme eastern Chihuahua (Webb 1960) may represent a disjunct population, a misidentification (Lemos Espinal and Smith 2007), or may possess faulty locality data (R. G. Webb pers. comm. 2008).

The individuals observed at Las Palomas in the Sierra Azul were located only 57 km south of the Arizona border in mesquite and oak grasslands very similar to that which is found in the Patagonia Mountains to the north in Arizona. A nearly continuous band of mesquite savanna and oak woodlands connect the Sierra Azul and the Patagonia Mountains. These savannas and woodlands are only interrupted by the Ríos Cocospera and Santa Cruz. Given the proximity to the Arizona border and the continuity of habitats, it is not inconceivable that a C. mentovarius might one day be found in Arizona.

Habitat: Rangewide, Johnson (1982) characterized the habitat preference of the species as “tropical or subtropical semiarid to semi-moist habitats (e.g. tropical deciduous forest, thorn forest, thornscrub, desert scrub, and tropical savanna)”. In Costa Rica, Savage (2002) noted its occurrence in open areas and thickets within lowland dry forest, premontane moist forest, and marginally in premontane wet forest. Hardy and McDiarmid (1969) reported this species in tropical deciduous forest and thornscrub in Sinaloa, especially in open areas, near cultivated areas, and in heavily grazed pasturelands. In Sonora, the majority (17) of records are from tropical deciduous forest, sometimes at the upper limit of that vegetation community. Seven occur in thornscrub. Another (21 km NE of Mazocahui) is in a thornscrub/mesquite grassland transition, and one (Las Palomas, NW slope of the Sierra Azul, Rancho El Aribabi) is in mesquite and oak grassland. The specimen from “Cueva Creek near Tres Rios” is from a riparian zone within oak woodland. One specimen (from near El Trigo E of Yécora) was found in an open oak savanna with pine-oak woodland on the adjacent slopes, another (Highway 16 27.4 km W of Maycoba) was found in a grassland/pine-oak association, and one from near La Otra Banda, Yécora, was in pine-oak woodland. Elevational ranges of Sonoran records are from approximately 36 to 1618 m, although most (18) are from 280-590 m.

Behavior: This is a fast, diurnal snake. It is much more terrestrial than either Coluber bilineatus or C. flagellum, although it is occasionally found short distances into shrubs or trees. Unlike the other two Coluber, which typically move away from people at high speed, the C. mentovarius encountered at Las Palomas (Figure 4) stood its ground with a writhing movement while facing S. Avila. However, similar to other Coluber, this species is aggressive and quick to bite. In Sonora, this species has been observed as early as 26 March and as late as 4 November. The month with the greatest number of records (11) is August. Coluber mentovarius feeds primarily on ground-dwelling lizards, such as Aspidoscelis, but will also take rodents, snakes, and probably birds and bird eggs (Savage 2002, Lemos Espinal and Smith 2007). Bogert and Oliver (1945) reported a Perognathus from a juvenile collected at Güirocoba. Juveniles may also take arthropods (Savage 2002). Reproductive behavior has not been studied in northwestern Mexico; however, elsewhere within its range, clutches of 16-30 eggs are laid in the spring months (Savage 2002).

Figure 4: Adult Coluber mentovarius at Las Palomas, Rancho El Aribabi, ENE of Imuris, Sonora (UAZ 56736-PSV). Photo by S. Avila.

LITERATURE CITED

Avila, S., C. Robles Elias, and J.C. Rorabaugh. 2008. Coluber (=Masticophis) mentovarius (Neotropical Whipsnake). MEXICO: SONORA. Herpetological Review 39(3):370.

Bogert, C.M., and J.A. Oliver. 1945. A preliminary analysis of the herpetofauna of Sonora. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 83(6):297-426.

Hardy, L.M. and R.W. McDiarmid. 1969. The amphibians and reptiles of Sinaloa, México. University of Kansas Publications, Museum of Natural History 18(3):39-252 + plates and figures.

Johnson, J.D. 1977. The taxonomy and distribution of the neotropical whipsnake Masticophis mentovarius (Reptilia, Serpentes, Colubridae). Journal of Herpetology 11(3):287-309.

Johnson, J.D. 1982. Masticophis mentovarius (Duméril, Bibron, and Duméril) Neotropical whipsnake. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 295:1-4.

Lemos-Espinal, J.A., and H.M. Smith. 2007. Anfibios y Reptiles del Estado de Chihuahua, Mèxico/Amphibians and Reptiles of the State of Chihuahua, Mexico. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mèxico y Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. 613 pp.

Liner, E.A., and G. Casas-Andreu. 2008. Nombres Estándar en Español en Inglés y Nombres Cientificos de los Anfibios y Reptiles de México/Standard Spanish, English, and Scientific Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of Mexico, Second Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles, Herpetological Circular 38.

Rorabaugh, J.C. 2008. An introduction to the herpetofauna of mainland Sonora, México, with comments on conservation and management. Journal of the Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science 40(1):20-65.

Savage, J.M. 2002. The Amphibians and Reptiles of Costa Rica: A Herpetofauna between two Continents, between two Seas. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London. 934 pp.

Tanner, W.W. 1985. Snakes of western Chihuahua. Great Basin Naturalist 45(4):615-676.

Utiger, U., B. Schätti, and N. Helfenberger. 2005. The oriental Colubrine genus Coelognathus Fitzinger, 1843 and classification of old and new world racers and ratsnakes (Reptilia, Squamata, Colubridae, Colubrinae). Russian Journal of Herpetology 12:39-60.

Webb, R.G. 1960. Notes on some amphibians and reptiles from northern Mexico. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 63:289-298.

Authors: Jim Rorabaugh, Sergio Avila, Carlos Robles Elías, and George Ferguson

Originally published in the Sonoran Herpetologist 2009 22(1):2-5.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][gap size=”30px” id=”” class=”” style=””][/vc_column][/vc_row]