[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Zebra-tailed Lizard (Callisaurus draconoides)

[/vc_column_text][gap size=”12px” id=”” class=”” style=””][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”290″ img_size=”large” alignment=”center” style=”vc_box_rounded”][vc_column_text]Zebra-tailed Lizard (male). ©2013 Dancing Snake Nature Photography[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”1918″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”img_link_large”][vc_column_text]Zebra-tailed Lizard, Yuma Co., AZ. Photo by Jim Rorabaugh[/vc_column_text][gap size=”12px” id=”” class=”” style=””][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”1919″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” style=”vc_box_rounded” onclick=”img_link_large”][vc_column_text]Zebra-tailed Lizard (adult, non-breeding female) venter, Cochise Co., AZ. Photo by Jim Rorabaugh[/vc_column_text][gap size=”12px” id=”” class=”” style=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”1922″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” style=”vc_box_rounded” onclick=”img_link_large”][vc_column_text]Juvenile Zebra-tailed Lizard. Photo by Young Cage[/vc_column_text][gap size=”12px” id=”” class=”” style=””][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”1923″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” style=”vc_box_rounded” onclick=”img_link_large”][vc_column_text]Zebra-tailed Lizard, Photo by Young Cage[/vc_column_text][gap size=”12px” id=”” class=”” style=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”1925″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” style=”vc_box_rounded” onclick=”img_link_large”][vc_column_text]Zebra-tailed Lizard, gravid female, venter, Cochise County, AZ. Photo by Jim Rorabaugh[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”1921″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” style=”vc_box_rounded” onclick=”img_link_large”][vc_column_text]Zebra-tailed Lizard, gravid female, Cochise County, AZ. Photo by Jim Rorabaugh[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”1924″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” style=”vc_box_rounded” onclick=”img_link_large”][vc_column_text]Adult male Zebra-tailed lizard, venter. Cochise County, AZ. Photo by Jim Rorabaugh[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_column_text]

Description

As I carefully inch forward to get a better look at the Zebra-tailed Lizard basking under a creosote, it arches its tail over the back and slowly wags it side to side (Figure 1), and then suddenly sprints away. This tail-wagging behavior is perhaps the most intriguing feature of the species and has given rise to one of its Spanish names, perrito (little dog). But, why does perrito wag its tail? This question has crossed the mind of nearly anyone who has observed the lizard, but not until 1989 was the question seriously addressed.

Figure 1. Zebra-tailed Lizard (Callisaurus draconoides) in a tail-wag posture. Yuma Co., Arizona. Photo by Jim Rorabaugh.

Oren Hasson, Richard Hibbard, and Gerardo Ceballos (1989), then at the University of Arizona, conducted a series of experiments on free-ranging Zebra-tailed Lizards along the Sonoran coast to test alternative hypotheses about the function of tail-wagging in the species. They examined four previously proposed hypotheses, all involving escape from predators: flash concealment (the sudden disappearance of a conspicuous flash when the lizard takes cover and ceases its tail wagging); distraction-autotomy (attracting attention to an expendable tail; Vitt and Ohmart 1977); conspecific warning (signaling other lizards of the presence of a predator); and pursuit deterrent (signaling to the predator a high level of alertness). They gathered data on tail-wagging frequency in various contexts including approaching and throwing a small stick. They conclude that the data reject the first three hypotheses and support pursuit deterrence (via signaling alertness) as the function of tail wagging in Callisaurus draconoides.

There is of course a cost associated with tail-wagging, that of signaling the lizard’s location to the predator. For Zebra-tailed Lizards this cost is likely offset by their speed and wariness. In California’s Sonoran Desert, sprints averaged 7.2 m per second (16.1 miles per hour) with a maximum of 9.7 mps (21.7 mph) and covered a distance of 9.1 m to 20.4 m (29.9 ft to 66.9 ft; Belkin 1961). Their sprint speed is increased by use of bipedal locomotion (Irschick and Jayne 1998). Wariness is greatest for lizards living in habitats with the least cover (Bullova 1994).

Zebra-tailed Lizards can afford the energy expenditure for sprints to escape potential predators. An average of 98.5% of their 10 hr activity period consists of remaining stationary and waiting for insect prey to enter their field of view (Anderson and Karasov 1981). Diet consists of a broad range of insects and other arthropods, with Diptera predominating in Death Valley (Kay 1977), Hymenoptera and Hemiptera at the Nevada Test Site, and Orthoptera and adult Coleoptera dominating the summer diet elsewhere in the species range (Pianka and Parker 1972, Vitt and Ohmart 1977). During spring they consume insects near flowers and are occasionally arboreal (Norris 1948).

Figure 2. Zebra-tailed Lizard (Callisaurus draconoides) in a basking posture, Sonora, Mexico. Photo by Eric Enderson.

In southern Arizona juveniles are sporadically active on warm days every month of the year (Roger Repp, pers. comm.). In Death Valley the onset of adult activity appears to be correlated with flowering of the creosote (Kay 1972). As with most desert-adapted lizards, activity is bimodal during the summer. It commences when the ambient temperature reaches 25°C (77°F), which is before sunrise in mid-summer (Kay 1972).

Mating takes place in April, May, and June, and clutch size averaged 4.6 (range 1-8) on the lower Colorado River (Vitt and Ohmart 1977) and 4.3 at Burro Creek (Smith et al. 1984) and at 14 localities from throughout the Southwest (Pianka and Parker 1972).

Half of the females lay more than one clutch a year (Vitt 1977). Hatchlings appear in late July and August and grow at the rate of 6.5 mm (0.3 in) per month (Pianka and Parker 1972). In Death Valley reproduction did not occur during an exceptionally dry year (Kay et al. 1970). At the Nevada Test Site, Zebra-tailed Lizards were found to be the most abundant of the four lizards present, with densities ranging from 1 – 15 lizards/ha and adult male home ranges averaging 0.35 to 0.50 ha (0.9 to 1.2 acres; Tanner and Krough 1974, 1975). Pianka and Parker (1972) considered the species to be a relatively uncommon desert lizard and its abundance at the 14 sites in the Southwest varied from 0.02 to 1.75 lizards/ha and was not correlated with any of the environmental factors measured.

Tanner and Krough (1974, 1975) witnessed predation by a Long-nosed Leopard Lizard (Gambelia wislizenii) and Coachwhip (Coluber flagellum). Sidewinders (Crotalus cerastes; Funk 1965) and Greater Roadrunners (Geococcyx californianus; Vitt and Ohmart 1977) also have been documented as predators on Zebra-tailed Lizards.

This is a thermophilic species with eccritic body temperature mean of 38.2°C (100.8°F), median of 39.2°C (102.6°F), and 50% of the values falling between 37.9°C (38°F) and 40.6°C (105°F; Brattstrom 1965, Clarke 1965, Packard and Packard 1970, Pianka and Parker 1972, Smith et al. 1987). Postures in the field reflect mean body temperature: prostrate with the head, trunk, and tail resting on the substrate, body dorso-ventrally compressed (Figure 2), 33.9°C (93°F); head and thorax elevated, forelimbs extended, tail and hind limbs resting on the substrate, 40.5°C (105°F); front and hind limbs extended, and body, toes, and tail raised above substrate (Figure 3), 42.7°C (109°F; Muth 1977a, 1977b).

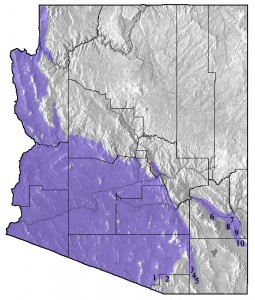

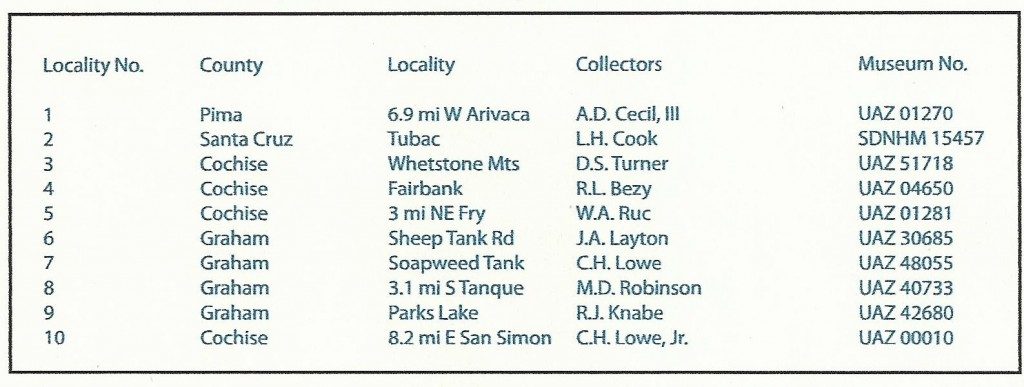

Zebra-tailed Lizards are widely distributed in the Sonoran, Mojave, and Great Basin Deserts from Cape San Lucas of Baja California Sur, north through Baja California and southern California to northern Nevada, south through southeastern Utah, Arizona, and Sonora to Sinaloa, and east to extreme southwestern New Mexico. The occurrence of the species in New Mexico was first reported by Lowe (1955) and recently studied by Baltosser and Best (1990). Zebra-tailed Lizards are largely absent from the grasslands and the Chihuahuan Desert of southeastern Arizona (Figure 4), but range up the San Pedro River valley to Fairbank and Fry, and east along the Gila River to Safford, and then south along the western flank of the Peloncillo Mountains to San Simon (Figure 4, Table 1).

On the basis of geographic variation in morphology, ten subspecies have been recognized, two of which occur in Arizona: the Eastern Zebra-tailed Lizard (C. d. ventralis) ranging across most of the state, and the Western Zebra-tailed Lizard (C. d. rhodostictus) in the west near the Colorada River. Studies of allozymes and DNA do not support recognition of these two subspecies (Adest 1987, Wilgenbusch and de Queiroz 2000, Lindell et al. 2005, Blaine 2008).

Figure 4. Distribution of the Zebra-tailed Lizard (Callisaurus draconoides) in Arizona. Numbers refer to localities documenting the limits of known distribution in southeastern Arizona (see Table 1).

The most distinctive subspecies, the Vizcaino Zebra-tailed Lizard (C. d. crinitus), is found on the wind-swept dunes of the Vizcaino Desert and has fringed toes and a distinctly flattened body. Although there is some evidence from mitochondrial DNA supporting the recognition of a separate lineage in the southern Baja California peninsula (Lindell et al. 2005, Blaine 2008), the Vizcaino Zebra-tailed Lizard does not to differ in nuclear markers (allozymes; Adest 1987) and populations intermediate in morphology have been identified (Grismer 1994, 2000).

The striking similarity of the Zebra-tailed Lizard to the Greater Earless Lizard (Cophosaurus texanus) in morphology and their shared tail-waging behavior suggest that these two species may be closest relatives (e.g., Earle 1961, Clarke 1965, Cox and Tanner 1977). However, DNA evidence indicates that Callisaurus is the nearest relative of all earless lizards (Cophosaurus + Holbrookia; Wilgenbusch and de Queiroz 2000). The type locality was originally listed by Blainville (1835) as “California” and was subsequently restricted by Smith and Taylor (1950) to “Cape San Lucas, Baja California.”

A Comáac (Seri) legend indicates if you become the enemy of a Zebra-tailed Lizard, it will use its power to inject something into your eyes that will turn them red (Nabhan 2003). The genus and species names are derived from Greek; Callisaurus, beautiful lizard; draconoides, dragon-like.

Acknowledgements.

I thank Tom Brennan and Erik Enderson for use of their photographs, George Bradley for his help and expertise and for access to the amphibian and reptile collections of the University of Arizona Museum of Natural History, and Kit Bezy and Kathryn Bolles for advice on the figures and for helpful suggestions on a previous version of this paper.

Literature Cited

Adest, G. A. 1987. Genetic differentiation among populations of the Zebratail Lizard, Callisaurus draconoides (Sauria: Iguanidae). Copeia 1987:854-859.

Baltosser, W. H., and T. L. Best. 1990. Seasonal occurrence and habitat utilization by lizards in southwestern New Mexico. Southwestern Naturalist 35:377-384.

Belkin, D. A. 1961. The running speeds of the lizards Dipsosaurus dorsalis and Callisaurus draconoides. Copeia 1961:223.

Table 1. Specimens documenting the limits of known distribution of the Zebra-tailed Lizard (Callisaurus draconoides) in southeastern Arizona. Locality numbers are plotted in Figure 4.

Blaine, R. A. 2008. Biogeography of the North American Southwest sand lizards. Ph.D. Dissertation. Washington University, Saint Louis, Missouri.

Blainville, H. M. de D. 1835. Description de quelques espèces de reptiles de la Californie précédée de l’analyse d’un système general de herpetology et de amphibologie. Nouvelles Annales Muséum National D’Histoire Naturelle 3:232-296.

Brattstrom, B. H. 1965. Body temperatures of reptiles. American Midland Naturalist 73:376-422.

Bulova, S. J. 1994. Ecological correlates of population and individual variation in antipredator behavior in two species of desert lizards. Copeia 1994:980-992.

Clarke, R. F. 1965. An ethological study of the iguanid lizard genera Callisaurus, Cophosaurus, and Holbrookia. Emporia State Research Studies 13(4):1-66.

Cox, D. C., and W. W. Tanner 1977. Osteology and myology of the head and neck regions of Callisaurus, Holbrookia, and Uma. Great Basin Naturalist 37:35-56.

de Queiroz, K. 1992. Phylogenetic relationships and rates of allozyme evolution among the lineages of sceloporine sand lizards. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 45:333-362.

Earle, A. M. 1961. The middle ear of Holbrookia and Callisaurus. Copeia 1961:405-410.

Funk, R. S. 1965. Food of Crotalus cerastes laterorepens in Yuma County, Arizona. Herpetologica 21:15-17.

Grismer, L. L. 1994. The origin and evolution of the peninsular herpetofauna of Baja California, México. Herpetological Natural History 2:51-106.

Grismer, L. L. 2002. Amphibians and Reptiles of Baja California, Including Its Pacific Islands and the Islands in the Sea of Cortéz. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

Hasson, O., R. Hibbard, and G. Ceballos. 1989. Pursuit deterrent function of tail-wagging in the zebra-tailed lizard (Callisaurus draconoides). Canadian Journal of Zoology 67:1203-1209.

Irschick, D. J., and B. C. Jayne 1998. Effects of speed, acceleration, body posture, and hindlimb kinematics in two species of lizard Callisaurus draconoides and Uma scoparia. Journal of Experimental Biology 201:273-287.

Kay, F. R., B. W. Miller, and C. L. Miller. 1970. Food habits and reproduction of Callisaurus draconoides in Death Valley, California. Herpetologica 26:431-436.

Kay, F. R. 1972. Activity patterns of Callisaurus draconoides at Saratoga Springs, Death Valley, California. Herpetologica 28:65-69.

Lindell , J., F. R. Mendez-de la Cruz, and R. W. Murphy. 2005. Deep genealogical history without population differentiation: Discordance between mtDNA and allozyme divergence the Zebra-tailed Lizard (Callisaurus draconoides). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 36:682-694.

Lowe, C. H. 1955. The eastern limit of the Sonoran Desert in the United States with additions to the known herpetofauna of New Mexico. Ecology 36:343-345.

Mosauer, W. 1936. The reptilian fauna of sand dune areas of the Vizcaino Desert and of northwestern Lower California. Occasional Papers Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan 329:1-22.

Muth, A. 1977a. Body Temperatures and associated postures of the Zebra-tailed Lizard, Callisaurus draconoides. Copeia 1977:122-125.

Muth, A. 1977b. Thermoregulatory postures and orientation to the sun: a mechanistic evaluation for the Zebra-tailed Lizard, Callisaurus draconoides. Copeia 1977:710-720.

Nabhan, G. P. 2003. Singing the Turtles to Sea. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

Norris, K. S. 1948. Arboreal Habits and Feeding of the Grid-Iron Tailed Lizard. Herpetologica 4:217-218.

Packard, G. C., and M. J. Packard. 1970. Eccritic temperatures of zebra-tailed lizards on the Mojave Desert. Herpetologica 26:168-172.

Pianka. E. R., and W. S. Parker. 1972. Ecology of the iguanid lizard Callisaurus draconoides. Copeia 1972:493-508.

Smith, D. D., P. A. Medica, and S. R. Sanborn. Ecological comparisons of sympatric populations of sand lizards (Cophosaurus texanus and Callisaurus draconoides). Great Basin Naturalist 47:175-185.

Smith, H. M., and E. H. Taylor. 1950. An annotated checklist and key to the reptiles of Mexico exclusive of snakes. Smithsonian Institution United States National Museum Bulletin 199:i-v, 1-253.

Tanner, W. W., and J. E. Krough. 1975. Variations in activity as seen in four sympatric lizard species of southern Nevada. Herpetologica 30:303-308.

Tanner, W. W., and J. E. Krogh. 1975. Ecology of the Zebra-tailed Lizard Callisaurus draconoides at the Nevada Test Site. Herpetologica 31:302-316.

Vitt, L. J., and R. D. Omart. 1977. Ecology and reproduction of lower Colorado River lizards: I. Callisaurus draconoides (Iguanidae). Herpetologica 33:214-222.

Vitt, L. J. 1977. Observations on clutch and egg size and evidence for multiple clutches in some lizards of the southwestern United States. Herpetologica 33:333-338.

Vitt, L. J., J. D. Congdon, and N. A. Dickson. 1977. Adaptive strategies and energetics of tail autotomy in lizards. Ecology 58:326-337.

Wilgenbusch, J. C., and K. de Queiroz. 2000. Phylogenetic relationships among phrynosomatid sand lizards inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences generated by heterogeneous evolutionary processes. Systematic Biology 49:592-612.

Author: Robert Bezy

Originally Published in the Sonoran Herpetologist 2011 24(3):23-26

For additional information on this species, please see the following volume and pages in the Sonoran Herpetologist: 2013 Dec:75-76.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][gap size=”30px” id=”” class=”” style=””][/vc_column][/vc_row]